Why do our southern shelters struggle and so many dogs die there?

This question in one form or another has been posed to me again and again in podcast interviews, on social media, in emails, and quite often, in person.

Before I say anything, I have to preface my words –

In many of the places where there are too many dogs suffering and dying, there are also people who struggle. And I’ve heard the sentiment that we need to take care of the impoverished people who are hurting before we can worry about the dogs.

I would counter that I believe there is enough compassion in this world to do both. We don’t have to care about one OR the other- we can want to help people AND save dogs. They are not exclusive. In fact, I would argue that dogs bring so much joy and healing to people, that saving them often can lead to helping people.

But I also believe we should save every adoptable dog.

Poverty is not an excuse to kill dogs or house them in cruel conditions or leave them on the streets.

I’ve visited over 120 shelters and rescues in 12 states, and many, if not most, were in poor counties or struggling cities. In the places where they were saving every healthy, adoptable dog, and housing them humanely, they had three elements in common:

1. Leadership committed to saving every dog. Period. That’s the most critical piece of this puzzle. I’ve often quoted, Dr. Kim Sanders, director of Anderson County PAWS in South Carolina, who told me that the way she took that shelter from killing 90% of its animals to killing 0% of its treatable animals, was to simply stop killing them. When you take that option off the table, she explained, you find others.

In Tennessee, West Virginia, Florida, North Carolina, Mississippi, and Alabama, I’ve visited shelters who have also changed their story, going from killing as many as 80 or 90% of their animals to saving every adoptable dog. Most often, it’s the shelter leadership that makes the decision, but in other places, it comes from volunteer or municipal leadership. That is the key—whoever is in charge of a shelter (and if you pay taxes, that means YOU), must decide that killing healthy, treatable, and adoptable dogs is not acceptable.

2. There has to be affordable, available veterinary access. We cannot spay/neuter our way out of this crisis, but without it, we will forever be chasing our tails. That doesn’t mean that veterinarians should give away their services. Most veterinarians got into this business because they love animals and want to help, but most veterinarians ALSO incurred huge debts, studied for years, work impossible hours, and function under tremendous emotional strain. Understandably, very few veterinarians would want to set up shop in a county where people don’t have the money or the motive to take their animals to the veterinarian. Or work with a shelter that has a practice of euthanizing animals for space. Add to that the current vet shortage in the US, and it’s clear why there are not enough vets in many poor rural areas.

Fixing this one is hard, but we must tackle it. In my book, One Hundred Dogs and Counting, I proposed one solution. Just as Teach for America helps supply teachers to under-resourced areas in exchange for forgiving college debt, we need something similar for veterinarians. If veterinarians served in under-resourced areas for a year or two in exchange for debt forgiveness, they would gain valuable experience and help solve a public crisis. Once more, they might even discover that they like shelter medicine, or living in the rural south, and decide to stay.

Another solution that progressive shelters embrace is to work with a community college vet tech programs or university veterinary schools. Once again, it’s a win-win, providing access and affordability to the shelter while students gain valuable experience. At one shelter in West Virginia, they are building classrooms across the street from the shelter to host the community college’s vet tech program.

3. The community must be engaged with the shelter. In the places we’ve visited where the shelter is saving all of its animals, there is an active volunteer community involved in the work of the shelter. Volunteers help care for the animals, offering exercise and enrichment. They are working on fundraising and support. Often there is a volunteer board advising the shelter or a separate 501c3 nonprofit group set up to support the shelter’s work. There is a foster program that keeps at-risk animals out of the shelter and offers breathing room for a crowded shelter. Regular events invite the community into the building and onto the property. The shelter is an inviting place with play areas for the dogs, trails for visitors to walk dogs, training classes and socialization opportunities to assist adopters in being successful with their pet, and some shelters even have a dog park on shelter property.

All of these places invite the public in and help the community view the shelter as theirs. In Georgia, one shelter employee told me, “This shelter belongs to the community—the building, the kennels, and the animals. Our door is always open.”

A shelter that does not allow volunteers inside because of liability concerns, or because they utilize inmates to do the cleaning (two practices we see everywhere we go), will never be a sustainable shelter that serves its community and saves every adoptable dog. The shelter belongs to the community and until they see it as an important resource that serves a critical purpose, the sad situation of too many dogs being euthanized, turned away, or warehoused, will continue.

It is possible to save every healthy, adoptable dog. I know it is because I’ve seen it done. It starts by recognizing the problem, by owning it. That’s why we work to raise awareness and resources—because without them, change cannot happen.

Until each one has a home,

Cara

If you want to learn more, be sure to subscribe to this blog. And help us spread the word by sharing this post with others. Visit our website to learn more.

You can also help raise awareness by following/commenting/sharing us on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, Tik Tok, and the Who Will Let the Dogs Out podcast.

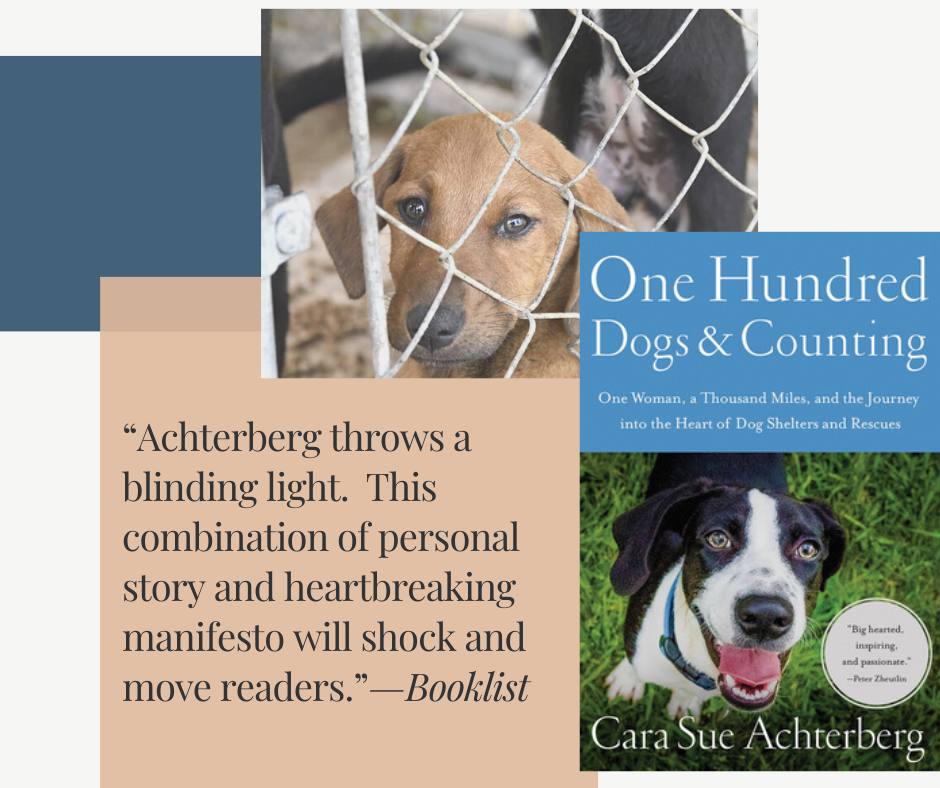

Learn more about what is happening in our southern shelters and rescues in the book, One Hundred Dogs & Counting: One Woman, Ten Thousand Miles, and a Journey Into the Heart of Shelters and Rescues (Pegasus Books, 2020). It’s the story of a challenging foster dog who inspired me to travel south to find out where all the dogs were coming from. It tells the story of how Who Will Let the Dogs Out began. Find it anywhere books are sold. A portion of the proceeds of every book sold go to help unwanted animals in the south.

For more information on any of our projects, to talk about rescue in your neck of the woods, or become a WWLDO volunteer, please email whowillletthedogsout@gmail.com or carasueachterberg@gmail.com.

And for links to everything WWLDO check out our Linktree.

Lin

Our local shelter (in a comfortable middle-class city) was having a hard time getting all the dogs walked at least once a day. A lot of former volunteers had retired or gone back to the office. So they just started a policy where adults can take a shelter dog out for a walk. They don’t have to go through all the volunteer training or commit to a schedule. The staff will bring the dog from the kennel, the adult leaves ID and gets some tips (don’t let the dog interact with other dogs, stay off your phone) and potty bags, and off they go.

It’s only been a couple of weeks, but the dogs are getting out, so 🤞🏽

Cara Achterberg

Brilliant! We have to find new solutions that make sense to all the issues that shelters face. We can’t stay stuck in the ‘we’ve always done it this way’ thinking.