Last week’s shelter tour was inspiring. To be honest, I had braced myself, expecting the worst, as headline after headline declares shelters everywhere are overwhelmed. And yet, we met amazing people making the most of tough situations.

For sure the toughest situation was in Marion County, South Carolina, where new director, Breanna, works miracles daily despite having nearly 200 animals in her care, a paid staff of herself, one full-time and one part-time employee (plus 3 prison camp ‘trustees’), no hot water (or drinkable water), and having all her dogs housed in outdoor enclosures in a flood zone.

Despite all of that, the Marion County dogs were happy and healthy, some of the friendliest and calmest dogs we met all week. The key to that magic is daily play groups. It underlined, once again, how much of a difference they make in the mental health of dogs.

If you check our Facebook page, you can find the live video I made in which all those dogs were quiet and attentive even while we walked through the kennel area. They came to the front of their kennels, accepted treats softly, and many even sat for the treats.

Contrast that with several of the other shelters where dogs were frantic at the sight of us, some doing the classic kennel spins that give away their mental state. It is not that the people running those shelters don’t love their dogs—it was so clear that they do—it’s just without a playgroup program, it’s really hard to meet the emotional and physical needs of so many dogs.

The absolute quiet in the Marion County kennels was a first for me. Another first for me was the lack of breed labels at Tazewell County Animal Shelter in Bluefield, Virginia. Ginny, the director at Tazewell, lists every single dog that comes through their facility as ‘mixed breed’, explaining that “if I wasn’t there at the point of conception, then I have no idea what breed this dog is.”

Breed labels are discriminatory and anyone in shelter and rescue work knows they can be the difference between life and death. Removing those labels, and instead describing dogs by their personalities, size, age, and preferences, will result in better adoption matches and more realistic expectations.

At Anson County Animal Shelter in Polkton, NC, I learned that enrichment is required by NC shelter regulations for any animal (dog or cat) that is held in a shelter longer than thirty days. Maureen, the director at Anson, showed me their enrichment logs documenting their efforts. Because plenty of dogs and cats linger for thirty days or longer, enrichment is a daily event that includes food-based activities (stuffed Kongs, feed balls, food games), olfactory experiences (scents, tracking game, find-it, nose work), Exercise (walks, fetch, agility, recall games), social contact (petting, brushing, sitting quietly), social contact (pair/group walks, play groups), plus lick mats, filled bones, bubbles, and even TV time.

North Carolina may still have some struggling shelters, but they are ahead of many states with their regulations for enrichment, required reporting, and certifying staff to give rabies vaccines. (Their regulation about not allowing igloo dog houses to have any chew marks or scratches, though, is ridiculous, imho.)

Unicoi County Animal Shelter in east Tennessee had one of the most unique models of operation. The county and both cities in the county (Unicoi and Erwin) pay a portion of the shelter’s payroll, and each appoints two citizens to sit on the shelter’s board. The shelter itself is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, which allows the staff to fundraise the $200,000 they need to run the shelter. It works for them, and thanks to an active group of volunteers, they are able to raise the money, but to me, it seems like a colossal waste of staff time/energy to raise money from the citizens whose taxes partially fund the shelter already. It would be a lot easier on everyone if tax money just fully funded the shelter.

Our last stop was at Franklin County Humane Society in Virginia. Besides their own intakes, the nonprofit shelter pulls from multiple small municipal shelters in Franklin County and the surrounding counties. They create breathing room in those shelters, which means they do not have to euthanize for space as often.

FCHS has created the safety net the area needs, and hopefully, their work, which includes a low-cost spay/neuter clinic, will reduce the flow of animals coming into the shelters. If all goes well, they’ll work themselves out of a job eventually (which should be the goal of every rescue).

I have to note that none of the shelters we visited euthanize for space, and none of them are open intake. They all work hard to keep animals in their homes—offering food pantries, counseling, sometimes brokering foster situations to avoid bringing another animal into their building. There are good arguments for managed intake, but to put it bluntly, it’s easy to be ‘no-kill’ shelter if you control when, how many, and what kind of animals you take in.

As so many shelters become managed intake, we need to be having the conversations about what becomes of the animals whose owners are turned away? Sure, some wind up as strays that Animal Control Officers bring in, but what about the others? What about the ones left at the mercy or lack of mercy of people who don’t want them?

If we are serious about helping all the unwanted and homeless animals, we have to find new ways of solving our crisis. Simply refusing to help is not a long-term solution. I read an article recently that said intake is down at our nation’s shelters. It’s not down because there are fewer animals in need. It’s down because shelters are not able to make room for more animals and the animals they do have are staying in the shelters longer.

Over the next few weeks, I’ll share more of the stories of the shelters we visited last week on our tour and the issues those stories raise for all of us to consider. I hope you’ll join the conversation and share your thoughts, questions, ideas, and solutions.

Until each one has a home,

Cara

If you want to learn more, be sure to subscribe to this blog. And help us spread the word by sharing this post with others. Visit our website to learn more.

You can also help raise awareness by following/commenting/sharing us on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, Tik Tok, and the Who Will Let the Dogs Out podcast.

To see our Emmy-nominated, award-winning short documentary, Amber’s Halfway Home, click here. If you’d like to see it on the big screen (along with other short dog films), check out the tour schedule of The Dog Film Festival, currently in art movie houses all over the country.

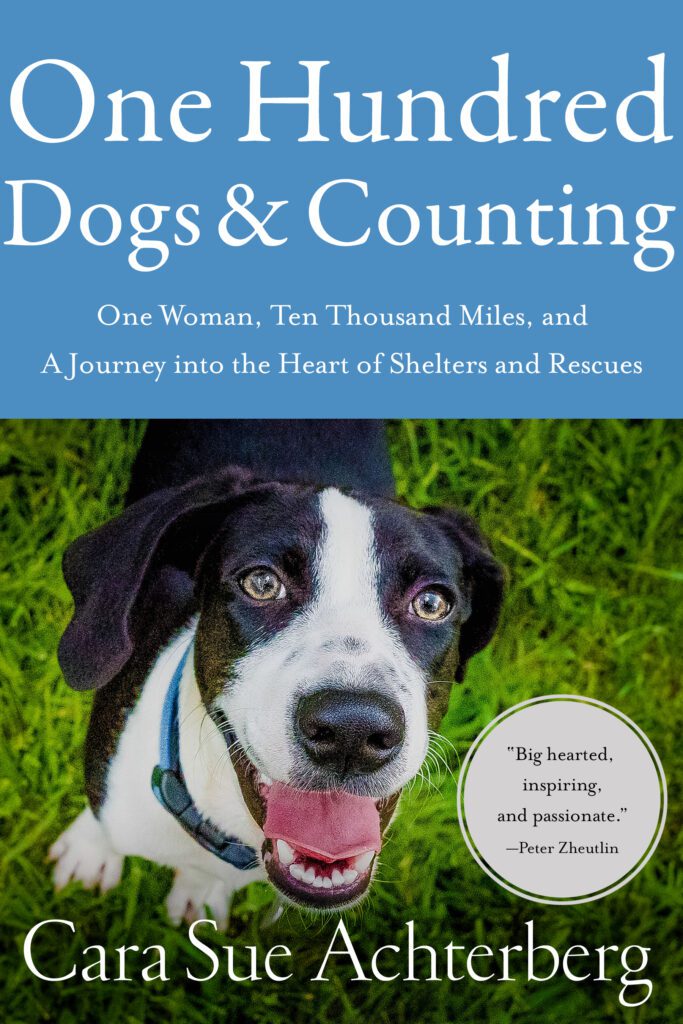

Learn more about what is happening in our southern shelters and rescues in the book, One Hundred Dogs & Counting: One Woman, Ten Thousand Miles, and a Journey Into the Heart of Shelters and Rescues (Pegasus Books, 2020). It’s the story of a challenging foster dog who inspired me to travel south to find out where all the dogs were coming from. It tells the story of how Who Will Let the Dogs Out began. Find it anywhere books are sold. A portion of the proceeds of every book sold go to help unwanted animals in the south.

For more information on any of our projects, to talk about rescue in your neck of the woods, or become a WWLDO volunteer, please email whowillletthedogsout@gmail.com or carasueachterberg@gmail.com.

Leave a Comment

Sign up for our newsletter

Sign up to have our latest news, grant updates, shelter visits, and more delivered to your inbox.

Share this:

Like this: