Montgomery Humane Society in Montgomery, Alabama is a large regional shelter working to find real solutions to its community’s struggle with unhomed animals. Their live release rate for dogs larger than twenty-five pounds is only 50%, but rather than hide that fact, they are transparent about it, inviting the community to not just own the problem, but also to be part of the solution.

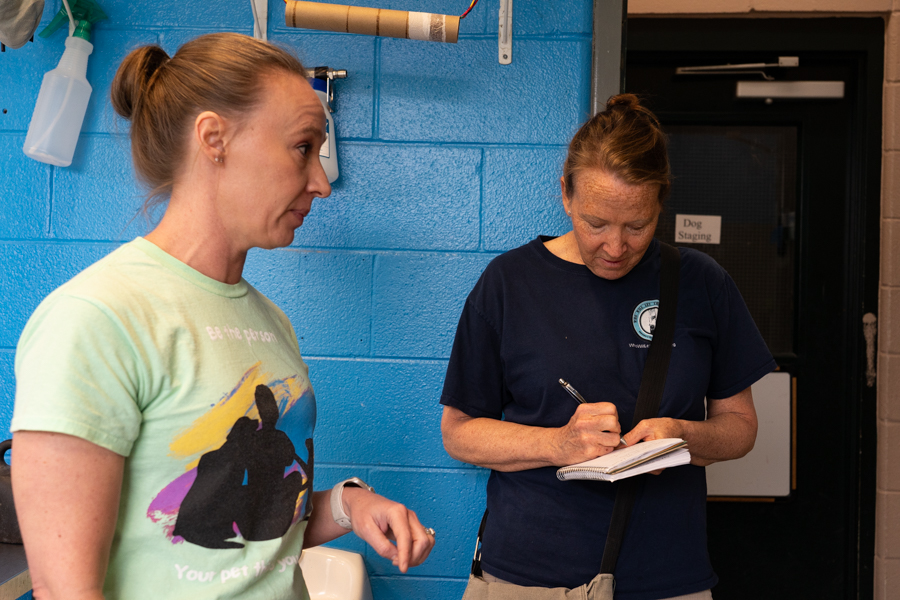

Kim, the Operations Manager is in her 17th year at Montgomery Humane Society in Montgomery, Alabama. She’s smart and compassionate and while her job is admittedly hard on a heart, she loves it. Kim grew up in Montgomery, but she’d never heard of the shelter until she lost her cat. While looking for her cat at MHS, she noticed the help-wanted sign. She needed a job with benefits, so she applied.

During our visit this past April, we also met Nenita, the volunteer coordinator who has been at MHS for nine years, and Christina, the Assistant Animal Operations Manager, who has worked at the shelter for fifteen years (since she was a teen). The affection and respect shown between these three women and other staff members we met was refreshing.

MHS is a bit of a hybrid. It handles the animal control contract for three municipalities (Montgomery City, Montgomery County, and Pike Road area). Those municipalities pay for the staff, ACOs, building, vehicles, etc., but care and programs are paid for by fundraising and grants. Basically, the cost of bringing the animals in is paid for by the municipalities, but the getting them out is paid for by the MHS staff.

MHS handles a large number of animals–six thousand last year. That number would be higher if not for their Shelter Intervention Program. Over the last two years, MHS has helped nearly 1000 families and 2000 pets by providing spay/neuter/vaccine/microchip services for community cats and low-income families.

MHS is technically open intake, although intake is managed to some degree. In addition to animals brought in through Animal Control, they accept strays from the community. Owners coming in to surrender animals must make an appointment two weeks out, and pay $25 to surrender it. Owners who cannot wait those two weeks, pay $125. If the animal is being brought in because of dangerous behavior, the shelter will pay for it to be euthanized at a local vet clinic, rather than have their staff euthanize it.

Because they are a large volume shelter, they have some hard numbers. They are completely transparent about those numbers – publishing them on their website. While their intake numbers have been slowly going down, their live release rate for dogs over 25 pounds remains at 50%.

Which makes it even more remarkable that their staff retention is so high. That’s thanks to intentional efforts to address compassion fatigue. Plus, demonstrates the importance of the work by paying a higher-than-average wage and offering benefits like health insurance, life insurance, 401K, and vacation time.

At any given time, the shelter has about fifty dogs fully vetted (including spay/neuter) and ready for adoption. They have adoption counselors who work with potential adopters to find the best match, along with flexible programs like the ‘foster field trip’ program where for a $25 fee (applied to the adoption fee) potential adopters can take home a dog and try it out for a day or three or even longer to be sure it’s the best fit before finalizing the adoption. Putting the foster field trip program into place has decreased their returns by 12-14%.

There may be tough decisions to be made every week, but the staff works hard together to give dogs every chance. At intake, dogs are fully vetted, microchipped, tested (and treated) for heartworm, scheduled for spay/neuter, treated for fleas/ticks, and given preventatives. Once in the kennels, they get out daily for walks and play groups, in addition to enrichment activities. Behavior evaluations are taken slow, allowing time for dogs to adjust to their new circumstances.

The shelter has a foster coordinator who manages about two hundred foster homes, while Nenita, the volunteer coordinator, manages the plethora of volunteers (238 adults and 113 in the Junior Volunteer Club). They get many of those fosters and volunteers from the military community nearby.

The shelter does not send many dogs out through rescues, and when they do, they seek out breed-specific and foster-based rescues. They would rather not send dogs from one shelter life to another shelter life.

As Kim explained, the lives being lost are not on the staff (even though she acknowledged the emotional toll it takes on them), this problem belongs to the community. While they work very hard to save every life possible, they are transparent about the fact that they cannot guarantee a live outcome.

I’ve been thinking about the situation since we pulled away from the shelter. MHS is a first-class facility with a dedicated, smart, passionate staff who truly care about their animals. They are working hard to provide spay/neuter for their community and prefer to educate rather than confiscate people’s animals. They have good policies, innovative programs, engaged volunteers. Their intake numbers are going down slowly, as they whittle away at the problem.

Could they save more lives if they transported more animals to rescues and shelters to the north?

They could.

But that’s not a solution; it’s a band-aid. It’s a band-aid that just about every southern shelter depends on, and one whose capacity to cover the problem is shrinking as rescues fill up, give up, or wear out.

This is a hard story, but it’s a truthful one, and MHS is not a sad place. The team cares deeply about the animals in their care and about their community and each other.

What do they need to turn the corner and become a sustainable shelter? A community that shares the responsibility for its animals. MHS offers spay/neuter, veterinary support, and education. They gladly provide resources like food, training, behavior advice, and even temporary foster care for an owner who is incapacitated.

The staff has successfully tackled the cat surplus through community cat programs, barn cat programs, and spay/neuter availability. Kim is searching for the tools to find a successful path to those kinds of save rates for their dog population.

As long as shelters depend on rescues to keep their numbers within ‘no-kill’ range, their community never has to own up to the problem, and they can continue to believe they are ‘saving them all,’ when in fact, they are just enabling everyone to avoid asking the hard questions and finding real solutions.

Until each one has a home,

Cara

If you want to learn more, be sure to subscribe to our email list to get the latest stories and solutions delivered to your inbox. And help us spread the word by sharing this post with others. Visit our website to learn more.

You can also help raise awareness by following/commenting/sharing our content on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and Tik Tok.

To see our Emmy-nominated, award-winning short documentary, Amber’s Halfway Home, click here. If you’d like to see it on the big screen (along with other short dog films), check out the tour schedule of The Dog Film Festival, currently in art movie houses all over the country.

Learn more about what is happening in our southern shelters and rescues in the book, One Hundred Dogs & Counting: One Woman, Ten Thousand Miles, and a Journey Into the Heart of Shelters and Rescues (Pegasus Books, 2020). It’s the story of a challenging foster dog who inspired me to travel south to find out where all the dogs were coming from. It tells the story of how Who Will Let the Dogs Out began. Find it anywhere books are sold.

For more information on any of our projects, to talk about rescue in your neck of the woods, or partner with us, please email cara@WWLDO.org.

And for links to everything WWLDO, including volunteer application, wishlists, social media, and donation options, check out our Linktree.

Leave a Comment

Sign up for our newsletter

Sign up to have our latest news, grant updates, shelter visits, and more delivered to your inbox.

Share this:

Like this: