This is the story of two shelters.

One publicly funded, open intake, run by animal control officers.

The other privately funded, managed intake, run by staff and volunteers.

I’ve often wondered if the average person knows the difference between a private or public shelter. And why some states and some counties have publicly funded shelters or pounds, and others don’t. Or why one county can have a public shelter and yet still have several private ones.

The hodgepodge that is animal sheltering in this country is too often random and unfair with shelters spanning a continuum from desperate dog pounds run by dogcatchers to million dollar buildings with million dollar budgets and employees with degrees in animal sheltering. Homeless dogs are subjected to the luck of the draw. They can’t migrate to a better county with better conditions. Where they land is where they land and too often that can be the difference between life or death.

In Franklin County, Tennessee, on the second Tuesday of our shelter tour, we visited two shelters ten minutes apart. They had one thing in common (besides too many dogs) – Jessica, a committed, fearless, dynamo who voluntarily helped one and had recently become an employee of the other.

We first met Jessica two years ago when we toured the Shelbyville City shelter in nearby Bedford county. She was a fulltime volunteer at the shelter, saving dogs with the help of her friend Cathy. They called themselves the Shelbyville Soldiers and their mission was to keep Shelbyville Shelter from killing dogs.

While we were there, we met the man who would eventually take over that shelter. He was a deputy in Shelbyville. He stood on the porch of the building on a sweltering day and basically called us Yankees who had come to meddle in their business. When I asked him (as I ask all the shelter directors I meet) if he had thoughts about why there were so many homeless animals in Shelbyville, he blamed it on the fact that houses and shopping centers had been built where once there had been fields. The dogs who historically had run loose began having run-ins with people and that became a problem. I’ve thought about that answer in the time since I heard it and I believe there is a little validity to it, but it doesn’t answer my original question.

What struck me besides the fact that he was the first rude southerner we’d met on our travels, was that he had no compassion for the dogs. He saw them as a problem to be dealt with not animals to be saved. Nancy has pointed out to me several times that some of the Animal Control Officers we meet view their job through the lens of police officer and deal with the animals as a threat to humans, a nuisance, even. Others take a more shelter directorly approach and view the animals as victims in need of protection and care.

At any rate, once the deputy took over the shelter later that year, Jessica was asked to leave. Policies changed. They weren’t in the business of shipping dogs north via rescue. Instead, they went back to killing unclaimed, unwanted dogs. Undoubtedly, this broke Jessica’s heart, but she is a rescuer and rescuers rescue. So she moved south to help Heather at Franklin County, which led to Animal Harbor which led to a job. (Since then Jessica tells me there is a small rescue that has begun working with Shelbyville to save some of the dogs, but she doesn’t know the details.)

Emily, the smart, articulate director of Animal Harbor told me, “Hiring Jessica was a no-brainer.”

She knew a rockstar when she saw one. And as the Adoption Coordinator at Animal Harbor, Jessica is in a position to help the dogs at the public shelter in addition to handling the adoptions at Animal Harbor. Her friendly, out-going, we-can-do-this attitude is saving lives all over Franklin County.

On that Tuesday in the pouring rain, we first headed to the Franklin County shelter. We found Heather, the same ACO we met on a visit two years ago, still working hard to save all the animals she can. A few things had changed. The promised overhang was finally installed to give the outdoor dogs a little protection from the glaring sun, and the cats now had fancy condos (from which they could easily escape, Heather told us with a laugh).

Like so many others, the pandemic had initially been good to Franklin County Shelter. They were able to save every dog through adoptions and rescue partners. But now, the shelter was full and no one wanted any animals. Nashville Humane was coming that week to pull a Shit Tzu dog, and Heather was pretty confident she could get them to take all the shelter’s puppies also. Lots of people were interested in the Bulldog who barely fit in his tiny kennel and looked miserable (but isn’t that the default face of most bulldogs?). But the rest? She was worried they would have to start euthanizing again.

There was one other bright spot—the Bissell Foundation had discovered Franklin shelter and been generous in sending supplies. Heather told us she had Cathy Bissell on speed dial. “Isn’t that something?” she laughed.

With the support of the Bissell Foundation and Jessica’s help pulling dogs for rescues and Animal Harbor, things did seem better. And yet, it was still one of the saddest places we visit. The small cement kennels inside are tiny, barely giving the dogs space to turn around, the smell and noise unbearable. The outdoor kennels are chainlink, crammed one beside the other and while these dogs at least have some fresh air, the stress level was high as we walked around and dogs lunged at the fences separating us from them and each other.

They still do not vaccinate on intake or deworm the animals. There is still no volunteer program at Franklin. No one coming to do enrichment or to walk the dogs. Heather said the county would never allow it because of liability and because they use inmates to do the cleaning. The dogs are still labeled with numbers instead of names. The shelter is basically a pound. Although when she does get locals wishing to adopt, Heather makes them pay for and secure an appointment to have their new pet spayed or neutered before leaving the building.

Franklin is a cramped, dark, smelly place that has an air of despair about it. Heather is doing her best, but she is only one person. The other two ACO’s, just like the last time we visited, did not appear to be involved in the care of the dogs.

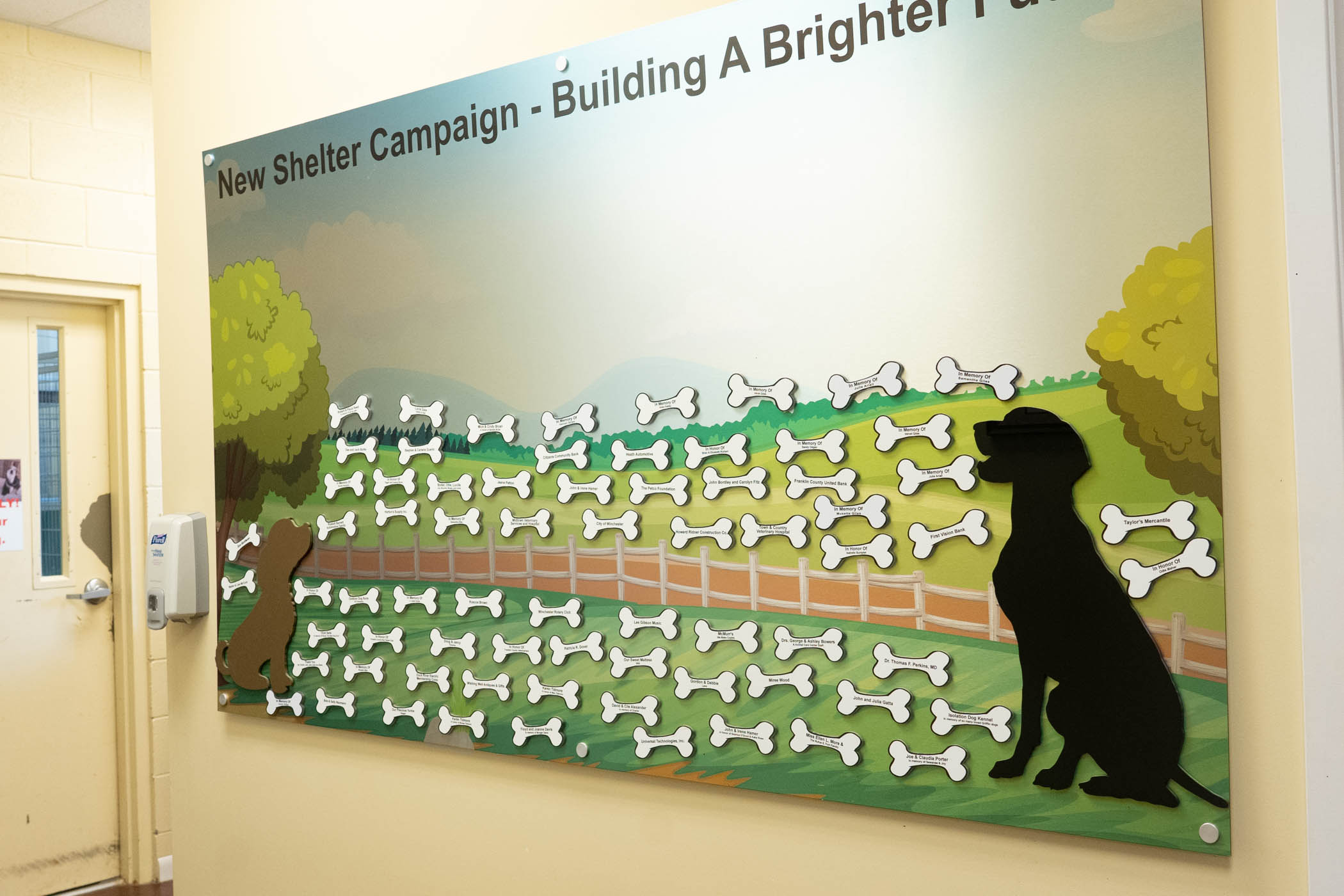

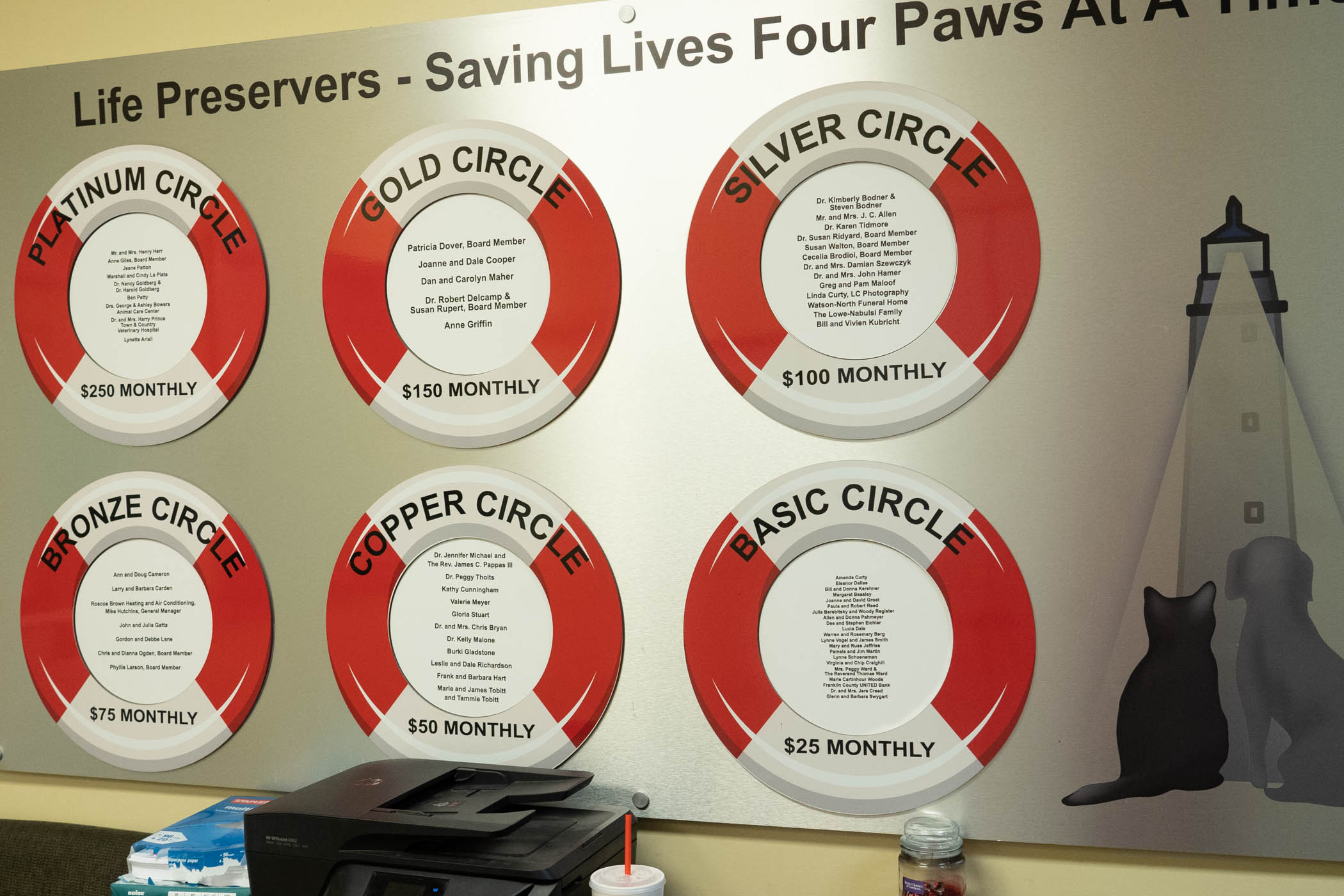

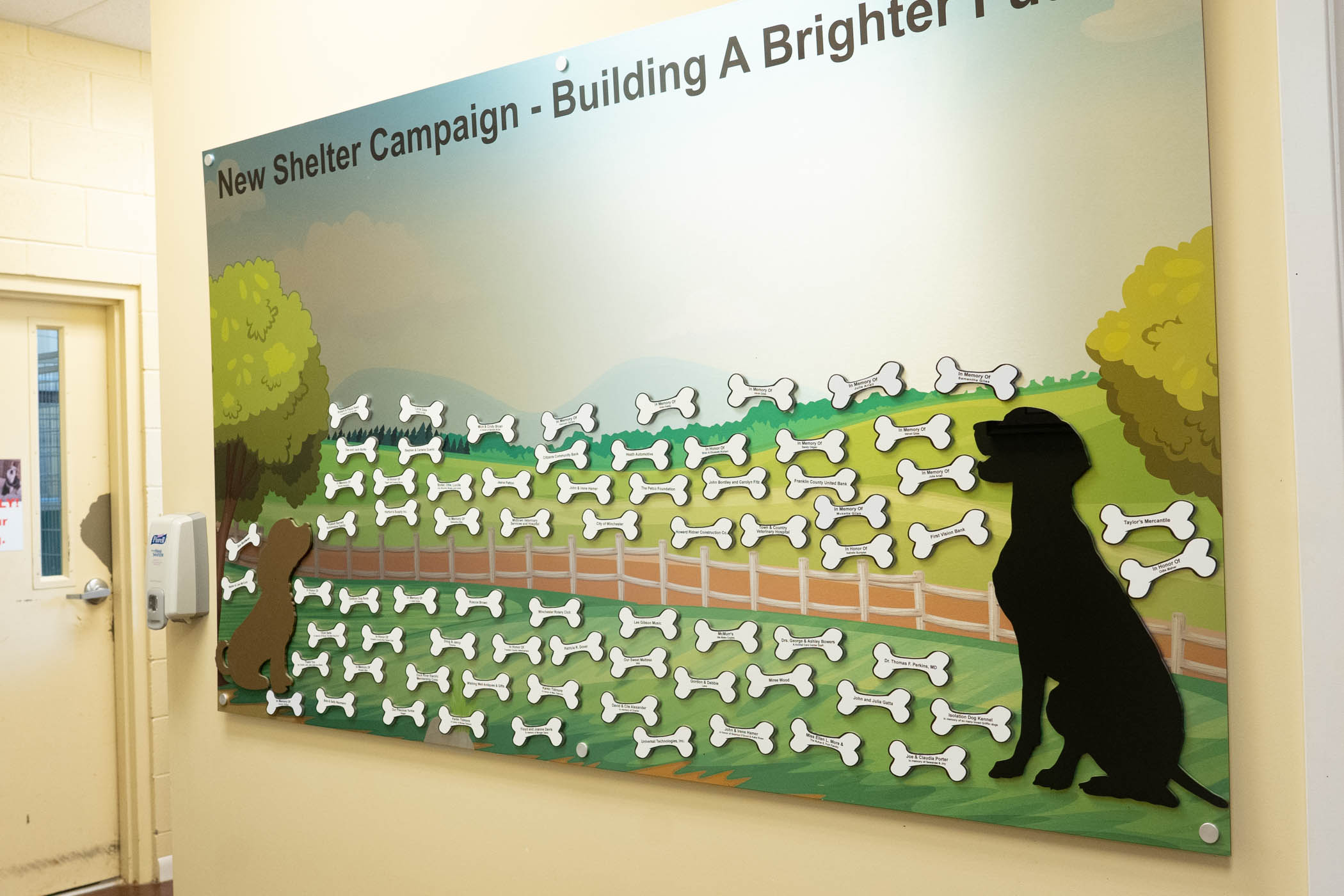

Contrast that with Animal Harbor. A bright, cheery place with murals and posters and friendly staff all working to keep the animals happy, healthy, and eventually find them homes. We met Krystina, who works as a trainer and kennel attendant and watched as she interacted with open affection for the dogs. We checked out the four cat rooms, visited with the dogs, and looked out over the open field in front of the building where AH planned to build an agility course for the shelter dogs to use.

We met Whitney, the wellness coordinator, who handles intakes. Animal Harbor manages their intake, which means they don’t accept more animals than they can handle. There are currently 100 cats on their waiting list to be surrendered. Owner surrenders for dogs were also way up. They were getting as many as 5-10 requests a day from owners wanting to surrender their animals.

But that’s the luxury of being managed intake—they can choose which animals to accept and when. Unlike Franklin County Shelter which must take in every animal brought to them (or found running loose in the county) whenever it turns up. And when there is no room, something has to go. If there is no rescue, no adoption, no foster program, that means killing animals.

Emily, the director of Animal Harbor, was working from home that day as she had recently been exposed to COVID, so we chatted by phone. When I asked her my question about the homeless animal problem, she said it was a lack of education and a mindset that drove the problem. People didn’t think of adopting a dog; spaying and neutering was often not a consideration.

Evidence of Emily’s excellent leadership, fundraising prowess, and commitment to the animals was everywhere we turned at Animal Harbor. It was a cheerful place. The staff were welcoming and seemed to truly enjoy their work. They were saving every animal in their care.

And that is the difference between private and public sheltering. Private shelters are by nature no-kill facilities usually run by animal advocates. They often crop up near public facilities to do what the publicly funded and government-run facilities can’t—save every adoptable animal. Instead of making our tax-funded shelters successful, individuals create new ones to do what the government can’t won’t. And that’s the part I don’t understand.

Why can’t we fix our broken system? Because there is no incentive to do it. Private shelters and rescues do incredible work and I, for one, am grateful for that work. But it is the work of these selfless organizations that enables our government to shirk its own responsibility to care for the homeless animals.

I’m not suggesting we close our private shelters; I am suggesting that the public demand more from the shelters they are paying their local government to run.

Until they do, there will always be a tale of two shelters.

Until each one has a home,

Cara

Please help us by subscribing to and sharing this blog. You can also keep track of us on Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube.

The mission of Who Will Let the Dogs Out (we call it Waldo for short) is to raise awareness and resources for homeless dogs and the heroes who fight for them.

You can learn more about what is happening in our southern shelters and rescues in the book, One Hundred Dogs & Counting: One Woman, Ten Thousand Miles and a Journey Into the Heart of Shelters and Rescues (Pegasus Books, 2020) which tells the story of a challenging foster dog who inspired the author to travel south to find out where all the dogs were coming from. It tells the story of how Who Will Let the Dogs Out began. Find it anywhere books are sold. A portion of the proceeds of every book sold go to help unwanted animals in the south.

Amber’s Halfway Home is a short documentary film we produced in partnership with Farnival Films. It tells the story of a remarkable woman and one day of rescue in western Tennessee. Selected for ten film festivals (to date), it is a beautiful, heartbreaking, inspiring story we hope will compel viewers to work for change. Watch it here.

For more information on any of our projects or to talk about rescue in your neck of the woods, or become a Waldo volunteer, please email whowillletthedogsout@gmail.com or carasueachterberg@gmail.com.

Naomi Johnson

Cara,

As I’ve said before, the main problem is the irresponsible, inhumane pet owners, puppy millls, and good ole boys who allow their animals to breed indiscriminately and dump them in the shelters or leave them on the side of the road. We need licensing laws and fines to “strongly encourage” owners to spay and neuter their pets. The problem is not going to improve unless we can stop, or, at least, slow it down at the source. I’ve been saving dogs (and cats) for over 50 years, and I saw the problem basically disappear in the North once people were hit in their pocketbooks for having dogs that were intact. There just aren’t enough rescues or adopters to save the incredible number dog that are continually being born in the southern states. The spay/neuter clinics do a great job, but for every animals they spay, there are dozens being born to the ones that aren’t spayed. The problem will not go away until it is controlled at the intake end. Hopefully, for the sake of the animals in the shelters, we see more shelters and staff like those at Animal Harbor.